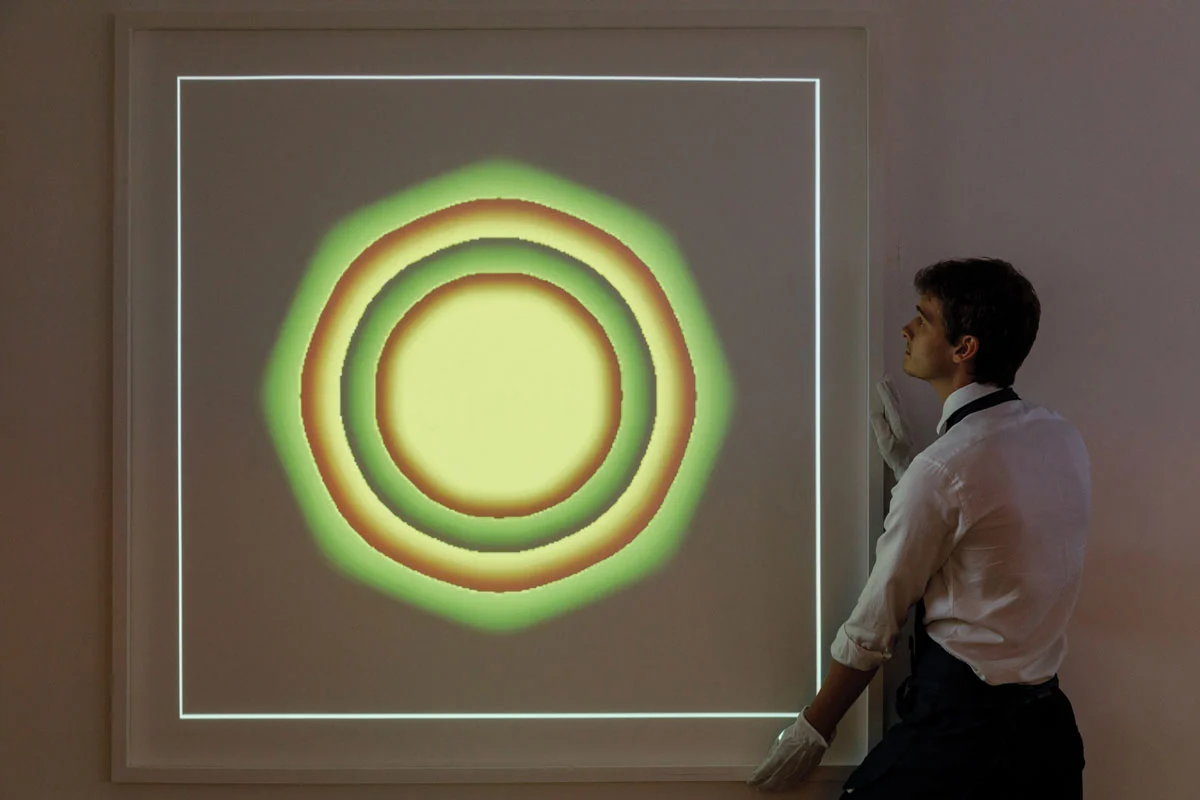

Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Sotheby's

A year ago, crypto and NFTs seemed unstoppable. In January, Jimmy Fallon and Paris Hilton hyped Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs on The Tonight Show and just days later FTX aired a blockbuster ad starring comedian Larry David during Super Bowl LVI.

We know how those stories turned out. As of this month, everyone is getting sued! Meanwhile, the Web3-heads who put their crypto into NFTs (or, god forbid, bought into crypto as it was peaking) are facing heartbreaking losses in value. The most interesting development, however, is the collapse of some grand vision of an alternate digital art market.

Once flipping NFTs for massive crypto gains was no longer a viable option, the question of what value is actually being offered to buyers has once again risen to the surface. This question wasn’t so hard to answer last year. In 2021, Mike Winkelmann (a.k.a. Beeple) sold his NFT Everydays: The First 5,000 Days at Christie’s for $69.3 million, making him the third most expensive living artist. The sale was proof that even if you didn’t quite understand what NFTs had to offer, they were valuable, and that was enough. Thousands of artists and collectors flooded into the market that Winklemann, Christie’s, and the buyer, Metakoven, brought into being with that sale.

But the greater promise of NFTs was that the technology could create a fairer economy for digital creators. The internet is built off digital content most often created without compensation to the creators who produced it. While popular creators can sometimes make a living selling merch or advertising products, it is difficult to impossible for them to make money off their primary product: digital content. NFTs, according to Web3 proponents, would change that by providing a medium of digital exchange and ownership that could also provide royalties on resale. For the first time, digital content would be the primary product, so the story went. Digital ownership had arrived.

But, as the crypto market has tanked, some uncomfortable truths have been revealed: when the unexpectedly crypto-rich are taken out of the dataset, there’s not actually that many people who are ready to buy digital assets that they’re used to getting for free. Worse, it’s become obvious that NFT tech was not capable of living up to its promises of permanence, royalties, and user-friendly trading. Artists have discovered that their supposedly blockchain-enforced royalties aren’t being honored and traders have found themselves repeatedly scammed and stolen from.

In the aftermath, major players and institutions are scrambling to address these issues and entice their remaining customers. Perhaps, once those adaptations shake out, we will finally be able to see what place, if any, NFTs will have in our online lives.

We’re (Not) All Gonna Make It

One of the most damaging blows to the vision of a NFT-enabled alternative digital art market has been the slow death of royalties.

In what many artists viewed as a major betrayal of the Web3 mission, platforms like Sudoswap, X2Y2, Magic Eden, Looks Rare, and even OpenSea decided to make royalties optional over the last six months. This move effectively made the entire NFT market royalty-free as anyone who wanted to re-sell an NFT could do so on one of the royalty-optional marketplaces, even if a creator created their NFT on a marketplace that supported royalties.

As OpenSea CEO Devin Finzer wrote in a November blog post about the situation, “To put it bluntly, the last few months haven’t felt WAGMI [We’re All Gonna Make It].”

This past September and through the fall, the discourse on marketplaces and royalties took a nasty turn as artists began to realize that royalties had never been enforced across marketplaces —even though ARTnews, for example, had reported on this issue as early as summer of 2021.

Basically, a smart contract, which includes royalty payment information, that has been made on one platform typically cannot be “read” by another platform. If someone bought a NFT on OpenSea, for example, and then sold it on another marketplace, royalties were most likely not paid out.

“I think the major misunderstanding was that creators did not realize this was not actually enforceable on chain,” Shiva Rajaraman, OpenSea’s vice-president of product, told ARTnews recently. “So we ended up with a situation where we’re both in a down market and you effectively have a rug pulled on a really important business model once marketplaces made these royalties optional. We knew we needed to look into a better way of enforcing this on behalf of creators.”

To that end, OpenSea announced a tool in November that makes royalties enforceable on-chain for new collections released in 2023, so long as creators select that option. This tool is a snippet of code that can be input into any smart contract that makes sure the NFT is only sold on platforms that support royalties. For creators who don’t use this tool, they can set royalties that buyers can choose not to agree to.

“Part of the web3 ethos is to let creators, not platforms, make choices as to how their business model should run,” said Rajaraman.

Others in the scene have a more cynical take as to why platforms have chosen to go royalty-optional.

“If you want to stimulate more wash trading, you’d have to kill the royalties,” Salah Zalatimo, CEO of NFT marketplace Voice, told ARTnews. Wash trading refers to when a trader sets up multiple wallets to sell NFTs to themselves, increasing the price each time to trick outside buyers into thinking that the asset is growing in value. If a platform mandated royalty payments, each time a hypothetical trader sold an NFT, they’d have to pay out a royalty fee each time – typically 10% of the sale price — thus disincentivizing the practice.

“There’s people sitting in boardrooms going ‘Well, how can we incentivize more market activity? Well, we can try to increase the profits to traders. How can we do that? One of the biggest hits to their profit is royalties, that’s 10%, so why don’t we just get rid of that?’” said Zalatimo.

Most platforms operate with low transaction fees that necessitate high trading volume in order to turn a profit.

In contrast, Voice, Zalatimo’s platform, has high platform fees and has committed to mandating royalties to creators. He said he hopes those moves create a more sustainable market and draw more creators to sell work on the platform.

Meanwhile, NFT platforms built on Tezos, a blockchain that became popular last year because it was more environmentally friendly and affordable than Ethereum, settled on a social fix for cross-platform royalty enforcement.

“What we see on other blockchains is that royalties are not being respected, and they think that a zero-royalty future is inevitable since there are so many ways to get around paying them, Ozzie Eryigit, the artistic director of fx(hash), a popular Tezos marketplace, told ARTnews. “That’s not the culture we have at Tezos.”

All NFT platforms built on Tezos — including teia, versum, fx(hash), and objkt.com, among others —have pledged to never offer 0% royalty fees in a gesture of solidarity with artists.

“If, as a community, we can stick to this law, there’s no need to be afraid of some other platform coming in with a 0% royalty situation,” said Eryigit. “Other blockchains want to make things as cheap and as easy for collectors, but artists have done so much in the past couple of years to receive royalties and we can’t forget that. Anyway, we believe that anything that goes against artistic values will damage revenues.”

Utility, Utility, Utility

As marketplaces struggle to prioritize creators, many have been on the hunt for use cases and perks that could draw customers back or, at least, convince the remaining ones to stay invested.

SuperRare, for example, created RarePass, an NFT that acts as a key to a subscription service that grants the holder one NFT a month, each by a different, popular artist. Additionally, each month, an artist creates three unique artworks randomly given to three RarePass holders. The Pass has been popular, with the first 250 offered selling out for a collective amount of $4.5 million, according to a press release sent to ARTnews.

Particle, which sells fractionalized shares of physical artworks as NFTs, a kind of Web3ified version of Masterworks, has also begun extending special benefits for holders of Particles. Co-founded by Loïc Gouzer, the ex-head of contemporary art at Christie’s, the company has attempted to give their tech-savvy clients entré to the art world by offering them fractionalized NFTs of works like Banksy’s “Love in the Air.” Now, however, Particle isn’t offering NFTs. Instead, Particles holders get a 25% discount on artworks sold at Phillips that Particle sourced for the auction house. In doing so, Particle has forfeited their commission from Phillips and is, basically, operating at a loss. But the offer is an important experiment in community building.

“What we’re trying to do with our NFT community now is really focus on building and understanding our community,” Charlotte Eytan, the director of Particle Foundation, told ARTnews. “We want to know who they are and what they want us to provide. We wanted to see if our collectors, who are mostly into NFTs, want to become collectors of physical art, tangible pieces.”

With RarePass and Particle’s initiative, NFT platforms appear to be narrowing in what profile-pic collections like Bored Ape Yacht Club already discovered: that NFTs’ most effective use case might be as a key to exclusive communities.

For BAYC, the 10,000 or so procedurally-generated avatars are the foundations for a community, which, in turn, is expected to create incentives or perks for belonging to that community. There are of course, the parties: for example, during NFT.NYC in June, Yuga Labs staged ApeFest, a festival featuring LCD Soundsystem that granted Ape holders entry. The festival’s draw, aside from the music, was the opportunity to network with other BAYC members, who theoretically are Web3ers, techies, and otherwise interesting people. But the main benefit for holding BAYC, or any other PFP collection, is the promise that by not selling, you’ll be first in line for any new releases or assets dropped by the collection’s team, fodder for the secondary market.

OpenSea has made a similar pivot. Whereas the platform initially started out as a place to buy art NFTs — one-of-one pieces of digital art — its bread and butter quickly became PFP collections like BAYC. OpenSea said that it is focusing on communities in 2023 and the content those communities are producing.

“Right now when you come to OpenSea, you see a grid of images and you make a discrete decision based on a collection or an item. What you’re gonna see a lot more of is storytelling and merchandising,” said Rajamaran. “We’ve been working to move from a secondary to a primary market.”

What we saw a lot of last year, however, was that NFT communities often struggled to come up with valuable perks and use-cases for their holders, especially at the pace that community members expected them.

Building the future of NFTs on continuously catering to massive communities — whether sourcing them physical art or pumping out digital assets — on top of producing effective governance, seems like an exhausting and risky move.

Web3 Makes Way for the Art World

Last year, crypto and NFT proponents were tut-tutting art institutions and established insiders for not embracing these novel technologies. Considering how quickly Web3 has unraveled, from unimaginably great, to bad, to worse, the art world’s slow adoption now seems quite prudent.

Surprisingly, however, the art world has had perhaps the most forward-looking attitude toward blockchain this year. While a vision of an alternative art market that takes places entirely online on NFT marketplaces has fallen apart, the art world has been building its own vision.

Since the NFT boom first kicked off in early 2021, startups with art world cred like Fairchain and Lobus offered established collectors and institutions a taste of the services blockchain could provide without forcing anyone to deal with crypto bros, an alluring compromise for the Web3 curious. But even these startups got a nasty shake when the crypto market went down. Then, just as the crypto market was officially declared dead, Art Basel’s parent company, MCH Group, along with the Zurich-based arts nonprofit LUMA Foundation, announced a blockchain they said was tailored for the art world: Arcual. Fairchain and Arcual have a similar appeal: blockchain-enabled art sales, managed by white-glove outfits, that offer artists, gallerists, and buyers authentication, tracking of provenance, and, for some, royalties.

For artist Mel Kendrick, father of Max Kendrick, the founder of Fairchain, there is a key, additional use case.

“With Fairchain, it’s less about the residuals, for me, but being connected with your art, knowing where it is,” Kendrick told ARTnews at his Lower East Side studio. Though it can be difficult imagining that one’s work has been sold so many times that one no longer knows where it is, Kendrick, who currently has a show at the Parrish Art Museum in Watermill, New York, said that has become the case over his long, successful career.

“There are so many pieces that I wanted to include in that show that I only have pictures of, if that. I have no idea where they are,” said Kendrick. It’s a source of pain that he and many of his artist friends and acquaintances have had to deal with, chalking it up to the price of business.

Now that Kendrick uses Fairchain, however, he’s hoping that won’t happen with the works he’s making and selling now as he tracks their movement from hand to hand, moving across an on-chain ledger.

Looking back over the past year, the potential of blockchain to enable a new internet, an alternative digital art market, and a metaverse, seems a little naive. The banal takes that dream’s place, as it seems most likely that blockchain tech will just be quietly absorbed by existing institutions and structures — the art world one among many.