It took exactly three days for someone to resurrect beloved Korean artist Kim Jung Gi after his death in early October at the age of 47. Not in flesh and blood, of course, but in code through the use of an AI image generator.

By October 6, a former French game developer known online as 5you announced that he had released a tool, based on popular open-source AI image generator Stable Diffusion, that could generate images in Kim’s iconic style with a text prompt. 5you described the tool as an “hommage [sic]” and encouraged users to “feel free to use it” so long as they “credit plz.”

Manga, anime, and comic book artists were universally outraged, with 5you telling Rest of World that he had received death threats from Kim’s fans and fellow artists. Some denounced the move as a tasteless ploy for publicity; others, meanwhile, read it as a premonition of the dystopian future that lay ahead—“they won’t let people die, they’ll work forever” read one popular comment on a TikTok. For many, 5you’s request for credit echoed a long line of white creators appropriating and then benefitting from Asian art styles.

But the controversy illuminates a truth long held by technology ethicists: New technology is not ideologically neutral; these tools latch onto and aggravate existing structural inequalities. Image generators like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, and others are poised to do the same, creating new avenues of exploitation while also reinforcing our existing biases.

While all artists stand to lose from AI, the Kim Jung Gi bot reveals how Asian artists in particular — long racialized as the robotic Other — are uniquely vulnerable to these tools as well as a new form of technologically-inflected Orientalism.

The Old and the New Orientalism

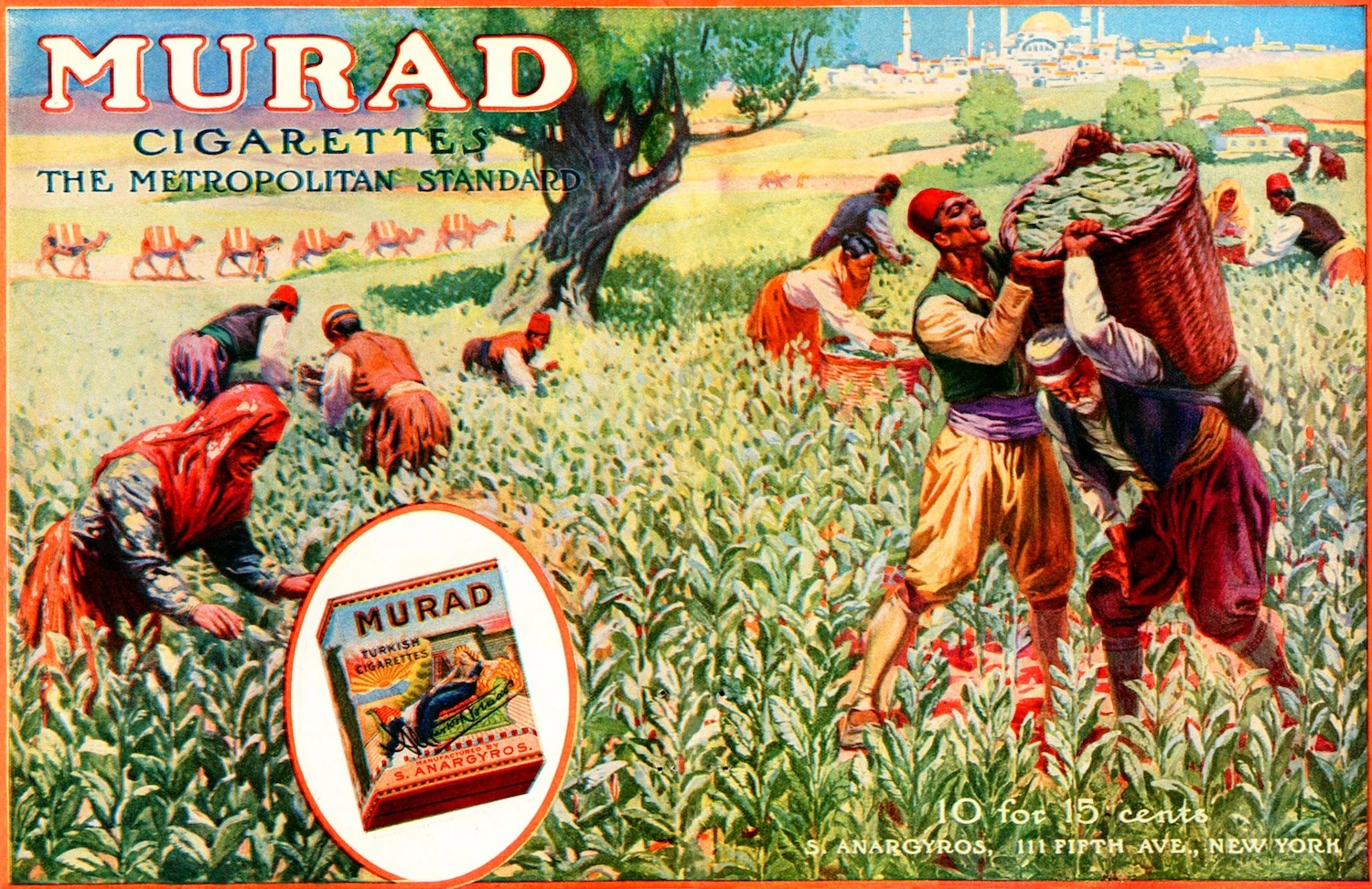

Historically, Orientalism in Western art was motivated by a vision of Asia as an archaic, traditionalist alternative to Europe— prone to barbarism, yet in contact with a mystic essence lost to those in modernity.

During the early period of Orientalism — typically considered the 18th and 19th centuries — it wasn’t uncommon for artists to adopt the styles and signifiers of these cultures from clothing and decor to artistic practices like printmaking, in the hopes of imbuing their work with a kind of exotic authenticity.

In the post-World War II era, however, Asia became an increasingly dominant player in the global economy and in the development of technology. The notion of Eastern backwardness could no longer hold in the face of its growing influence, and so a new myth arose to rationalize the superiority of the Western subject while making sense of this global reconfiguration. Asian peoples began to be depicted in the media as essentially robotic— automata capable of fine-tuned execution and coordination, but lacking the sort of individual creativity and spirit that defined the Western subject.

As the theorist Wendy Hui Kyong Chun wrote in her 2019 study on “High-Tech Orientalism,” these depictions protected whiteness’ hegemony over the human by “jettisoning… the Asian/Asian American as robotic, as machine-like,” while explaining Asia’s technological proficiency in dehumanizing terms that justified their continued exploitation.

This framework has since been dubbed “techno-Orientalism,” where the traditional and premodern imagery that once stereotyped Asia is replaced by “hyper technological terms,” as the editors of an essay collection on the subject note. In this formulation, Asian people are racialized using the language of machines, as industrious, hard-working, and functionally competent, yet hollow and lacking personality, while their art is rendered “soulless and mechanical.”

Techno-Orientalist stereotypes have become commonplace in mainstream media, from Hollywood blockbuster films like Blade Runner, with its Tokyo inspired cityscapes and Asian holograms, to musicians like Grimes, who frequently draws on Asian iconography in her flirtations with technoscapes, to video games like 2022’s Stray, which depicts a thinly disguised Kowloon Walled City populated solely by robots. White creators in nearly every medium have and continue to use Asianness to symbolize robotic futurity, and vice versa.

The Logical End of Techno-Orientalism

5You’s model simulating Kim Jung Gi and his art style is just the latest evolution in this twisted association between Asian bodies and roboticism. Finally, the Asian artist, long racialized as mechanistic, is reproduced via technology. The Asian artist is fully realized as a machine, thrust into the public as a product to be exploited and consumed. It’s not just their art, but the artists themselves that are now appropriated— pacified, transformed into a pure tool, made manipulable for anyone who might be so inclined (as long as they give the developer credit, of course).

Though one might point out that historically famous white artists have also been simulated by image generators, the speed with which Kim was mechanically refashioned after his death gestures towards an underlying attitude that already saw him as mechanistic to begin with.

In September, Jennifer Gradecki, a Northeastern University art and design professor, said in an interview about the future of artists that “creativity is actually the one thing that isn’t going to be able to be automated” in the future. Gradecki may have meant to reassure artists, but for Asians, a group often denied claims to creativity — and characterized at best as effective replicators, but rarely creators or originators — her statement rings like a warning for how these tools might push us further towards the margins and alienate us from our art.

Jet Li, for instance, voiced precisely this fear when he explained in 2018 that his refusal to work on The Matrix franchise stemmed from the fact that the filmmakers wanted Li to “record and copy all [his] moves into a digital library,” meaning that the movements of his body, honed during a lifetime of training, would become someone else’s intellectual property forever.

When you’re already seen as mechanistic, the reproduction of your bodies and art through machines isn’t seen as theft, but simply the next logical step.

Fighting the AI Future

We shouldn’t simply resign ourselves to this alienated future — and many artists aren’t, instead using a range of disciplines to interrogate the boundaries between human and machine creativity.

Chinese Canadian painter Sougwen Chung, for example, incorporates a robotic arm into her art-making practice. As the robotic arm and Chung read each other’s brush strokes and respond in an ever-evolving dance, the machine collaboration centers her body— rather than divorcing her from it— by highlighting the physical performance between these organic and inorganic beings.

Meanwhile, last year, Korean American artist Anicka Yi, installed a series of floating “biologized machines” — giant ovoid airborne structures that suggest jellyfish — in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. The installation contained another component often included in Yi’s practice: a particular aroma that changed week to week based on different time periods. One scent profile was meant to evoke the bubonic plague. Yi’s semi-autonomous robo-organisms challenge the cold, sterile notion of artificial intelligence as disembodied “pure cognition” by integrating them in natural forms, while her olfactory scent-scapes serve as a carnal reminder of embodiment.

Korean American filmmaker Kogonada has challenged techno-Orientalist ideology directly in his latest film, After Yang. In the film, starring Colin Farrell, Jodie Turner-Smith, and Justin Min, a father goes on a mission to repair his daughter’s non-responsive robotic “big brother” and caretaker, Yang. The film is a profound meditation on the figure of the Asian robot in the sci-fi genre, complicating this archetype beyond recognition and making space for something new.

The impact of these technologies is not yet written, but if history is to serve as a guide, new tools tend to carry on the mistakes of the past without direct intervention. Liberating these devices from their dehumanizing potential will require us to challenge and reimagine the frameworks we use to navigate the oppressive binaries of man and machine and East and West.

Only then might we truly live up to Kim Jung Gi, who hoped that these technologies would help us pave new paths forward— enabling us to express ourselves more clearly and ultimately “make our lives more diverse and interesting.”