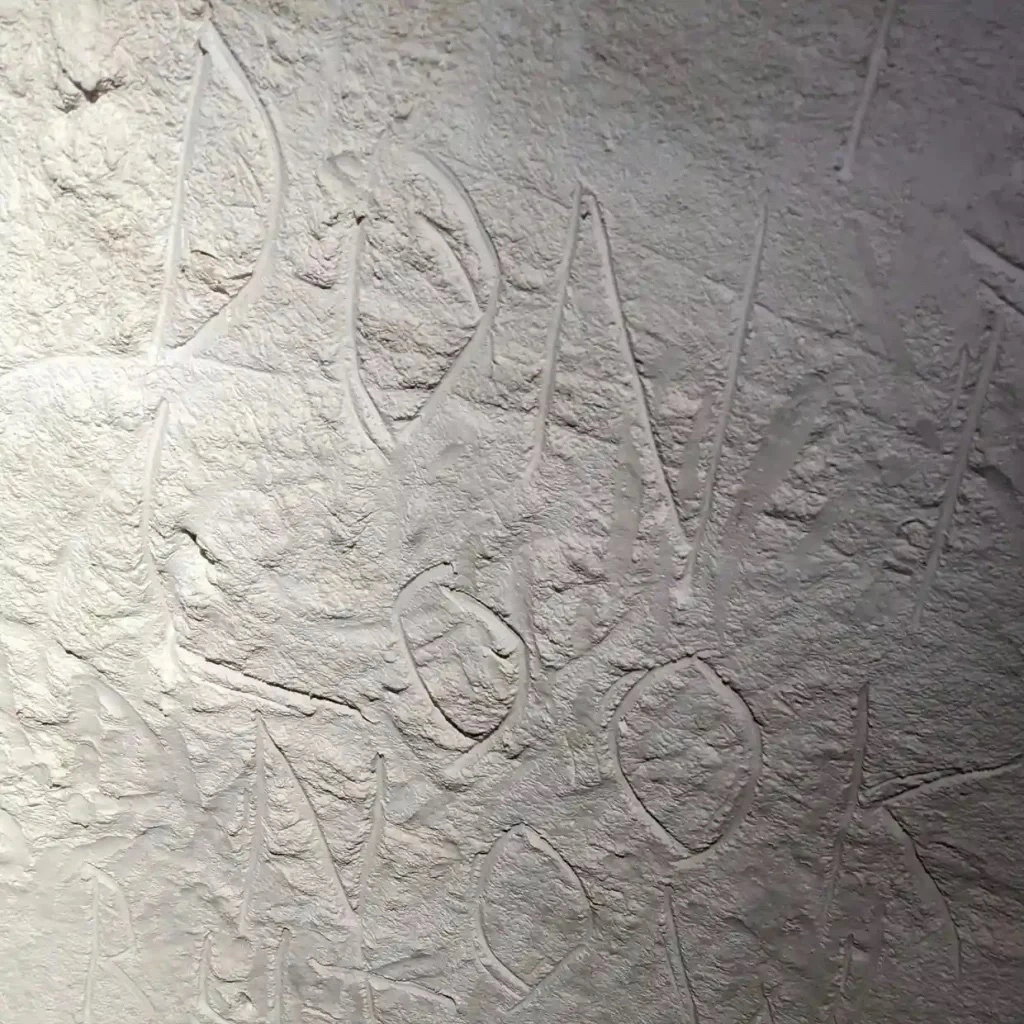

Vandals have destroyed an ancient Aboriginal artwork at a sacred cave in South Australia, reigniting frustration over the lack of protection at the heritage-listed site. Authorities have decried the destruction as a “massive, tragic loss” to artwork that was “unique in Australia”.

Vandals broke into Koonalda Cave on Nullarbor Plain by digging under a steel gate and scrawled graffiti across the stone carvings, writing “don’t look now, but this is a death cave,” authorities said. An entire section of the structure was destroyed.

“The vandals caused a huge amount of damage. The art is not recoverable,” Keryn Walshe, an archaeologist of ancient Aboriginal culture, told theGuardian Wednesday. “The surface of the cave is very soft. It is not possible to remove the graffiti without destroying the art underneath. It’s a massive, tragic loss to have it defaced to this degree.”

Kyam Maher, South Australia attorney-general and aboriginal affairs minister, told Australia’sABC Radiothat the incident “is quite frankly shocking” and called for a “severe penalty” for the guilty parties. Under local laws, damaging an Aboriginal heritage site could result in six months prison time or a fine of A$10,000 ($6,700).

The cave belonged to the Mirning people, who have a distinct sculptural practice that dates to 30,000 years ago. From that time until now, they regularly visited the sacred cave. The location was listed in 2014 as a national heritage site and is overseen by the Department for Environment and Water and the Far West Coast Aboriginal Corporation, which includes the Mirning people. However, the Mirning are unable to safeguard the site themselves, as their traditional custodianship is not yet acknowledged in Australian law. To even access the site, they need a key from SA’s environmental department.

A spokesperson for the SA government told the Guardian that the vandalism was “shocking and heartbreaking”.

“Over recent months, the South Australian government has been consulting Traditional Owners and other stakeholders on developing a comprehensive plan to better protect this important site,” said the spokesperson, adding that “The existing fencing and general difficulty in accessing the caves deters the vast majority of visitors from trespassing. Live monitoring of the site via closed circuit cameras is being considered to better protect the cave.”

Experts andindigenous activists, however, have called for immediate action, warning the SA government that the metal fence, installed in 1980s, was inadequate protection and vandals had already defaced the site to a less extreme extent.

“The failure to build an effective gate, or to make use of modern security services, such as wildlife monitoring cameras that operate 24/7, has in many ways allowed this vandalism to occur,” Clare Buswell, chair of the Australian Speleological Federation’s Conservation Commission, wrote in a submission to the Aboriginal lands parliamentary standing committee in July, theGuardianreported.

Koonalda Cave is only the latest loss of Aboriginal culture to wanton destruction. In 2020, the mining company Rio Tinto detonated the 46,000-year-old Juukan Gorge rock shelters to expand its iron ore mine. In a submission to a Senate inquiry on the destruction,Rio Tintoacknowledged that “various opportunities were missed to re-evaluate the mine plan in light of this material new information” on the importance of the shelters.

Senior Mirning elder, Uncle Bunna Lawrie, told the BBC that the vandalism was another example of “the constant disrespect” his people suffer.

“It’s abuse to our country and it’s abuse to our history,” he said. “What’s gone is gone and we’re never going to get it back.”