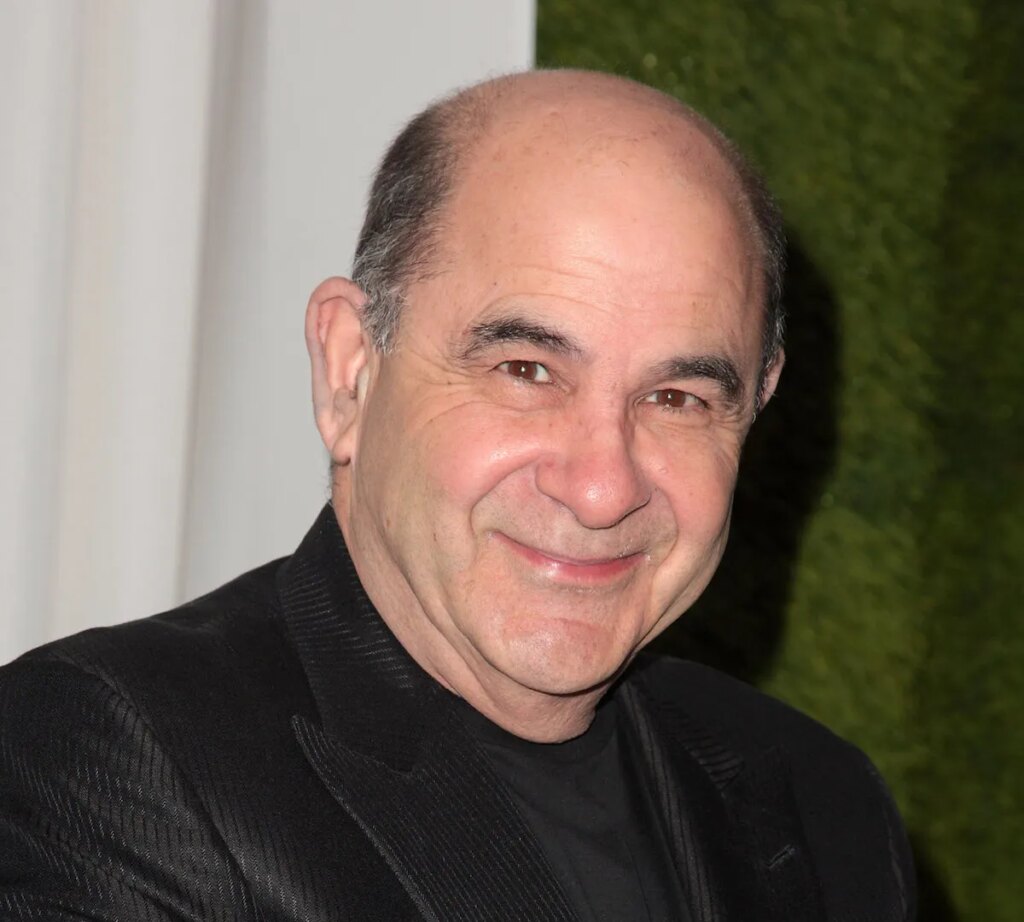

Joel Shapiro, an acclaimed Post-Minimalist sculptor whose work explored shifts in scale and perception, died on Saturday at 83. His death was announced on Sunday by Pace Gallery. The New York Times reported that he had been battling acute myeloid leukemia.

Shapiro’s work has been seen widely, in particular his figural sculptures made from bronze and aluminum elements, which have been seen everywhere from the United States Holocaust Museum to the rooftop of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Though steeped in the haughty concepts that guided art-making during the 1960s and ’70s, these sculptures are also quirky and whimsical, with limbs that appear to leap and flail.

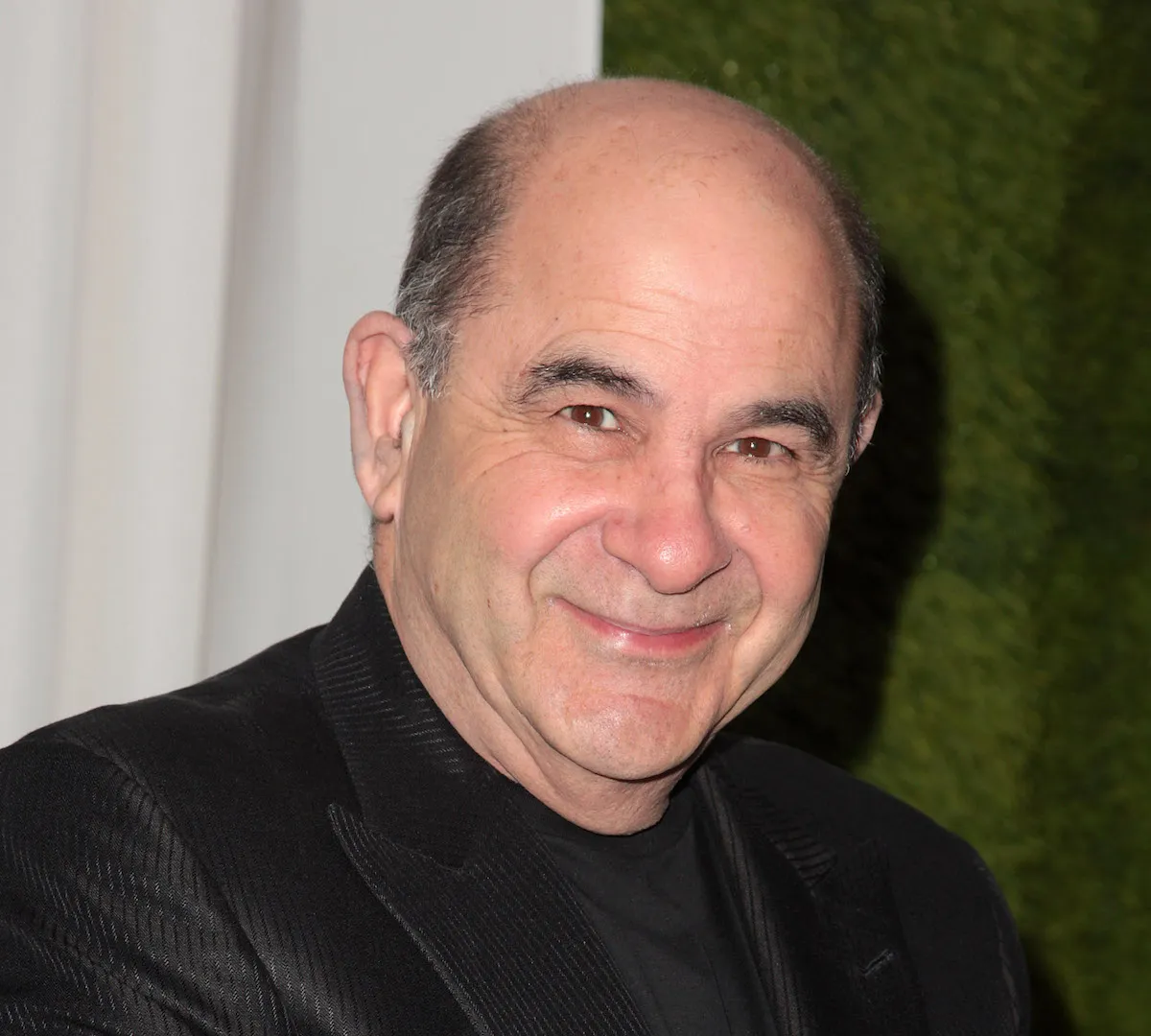

Often, these sculptures were made first in wood and then translated to metal. Some of them were painted in vibrant colors—something that would have been anathema to Minimalism, the movement that was dominant in New York during the early 1970s, when Shapiro’s work gained the attention of critics and dealers.

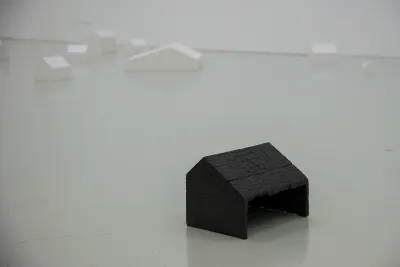

Shapiro’s earliest works relied on the language of Minimalism, then subverted it. He made a series of drawings made by inking his finger and pressing the tip to a piece of paper, resulting in marks arranged to recall a Minimalist grid, except that Shapiro’s rows were irregular and unruly.

He also relied on industrial materials, another Minimalist hallmark, but his were utilized in ways that appeared to undermine conventional logic. Untitled: 75 lbs. (1970) comprises a bar of magnesium and a bar of lead, both exhibited on the floor. Though the two bars each weigh exactly 75 pounds, the one metal is far more dense than the other, so their relative sizes differ greatly, and they appear unlike.

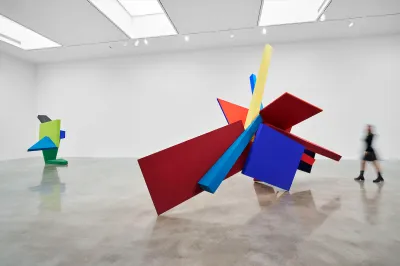

During the ’70s, at Paula Cooper Gallery, the New York space that showed Shapiro for almost the entirety of this career, the artist exhibited objects that further surprised the eye—tiny houses in cast iron and bronze, itty-bitty chairs easily tipped over with a little kick.

“I think they insisted on their own obdurate sense of self, in spite of the space surrounding but at the same time they’re a part of it,” Shapiro told the Brooklyn Rail in 2007. Their smallness was a reaction to the monumentality of Minimalism, and their recognizable forms differentiated them from the abstract sculpture seen widely in New York at the time.

By the ’80s, Shapiro’s work had started to appear more figural, putting him on the path to creating his oversize sculptures resembling figures whose limbs are made from beams of metal. “I am interested in those moments when it appears that it is a figure and other moments when it looks like a bunch of wood stuck together,” he said.

Although Shapiro’s art expanded greatly in height, with works in a recent show at Pace Gallery in New York towering high above viewers, he seemed squeamish about the notion that he had finally made art on a monumental scale. “Yes, I’ve made big things,” Shapiro told a Bomb magazine interviewer in 2009. “They’re not colossal. They could be monumental. I’d like to think that they’re not too bloated.” Asked for clarification, he said, “bloat is a disease of sculpture.”

Joel Shapiro was born September 27, 1941, in New York. His father was an internist, and his mother a microbiologist; they raised Shapiro and his sister, Joan, in the Queens neighborhood of Sunnyside after World War II.

Shapiro attended New York University, his parents’ alma mater, with the intention of becoming a doctor himself, but, as he put it in the Brooklyn Rail interview, “the only thing I was any good at was making art.” He said that he had confirmed as much in therapy. After graduating in 1964 with a BA in liberal arts, he served in the Peace Corps from 1965 to 1967 in southern India. In the Rail Interview, Shapiro credited the experience with having “heightened my sense of the hugeness and variety of life in general, but also, the possibility of actually becoming an artist became very real to me for the first time.”

He then returned to NYU, this time in the graduate art program—which accepted him despite his lacking an undergraduate degree in the subject. Shapiro was at the time married to Amy Snider; they had one daughter, Ivy, and divorced in 1972. He also took work at the Jewish Museum, where he helped install exhibitions and polish silver objects in the institution’s collection.

Shapiro’s big break came in 1969 with “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials,” a Whitney Museum exhibition curated by Marcia Tucker that helped formalize the Post-Minimalist art movement, with a checklist that also included Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman, and Rafael Ferrer. Shows with Paula Cooper followed, and Shapiro featured in the inaugural 1973 exhibition of the Clocktower Gallery, which ultimately became the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, now known as MoMA PS1. In 1978 he married Ellen Phelan.

His work has been seen in some of the world’s biggest museums and galleries, among them Pace, which has represented Shapiro since 1992.

“For over 30 years, it has been my honor to represent Joel Shapiro and to count him as a close friend,” Arne Glimcher, Pace’s founder, said in a statement on Sunday. “His early sculptures expanded the possibilities of scale, and in his mature figurative sculptures, he harnessed the forces of nature themselves. With endless invention, the precariousness of balance expressed pure energy—as did Joel. I will miss him dearly.”

Save for just a few of his pieces, Shapiro never titled his art. Asked why by the Rail, he said, “I’m not much of a poet. Form is its own language.”