The circus has rolled into town. Frieze London and Frieze Masters open their doors to the VIPs today, but are London’s fairs fast becoming an amuse-bouche for the feast that will be Art Basel Paris next week? Many think so. The art market has been cooling for a while, and the temperature change is particularly acute in the UK with several galleries axing staff or folding. London’s grip on big ticket sales is also loosening. But the cultural institutions, houses, and Frieze remain defiant in the face of new competition across the channel. Talk of direct competition with Art Basel Paris is being played down. Eva Langret, Frieze London’s artists director, recently said she thinks “there’s space for the two cities to be great together.”

For anyone who wants a break from the drama, there are loads of impressive gallery and institutional exhibitions opening in London this week. Despite all the talk of London’s art market decline, the city remains a major player. Below a look at the best on offer around town.

-

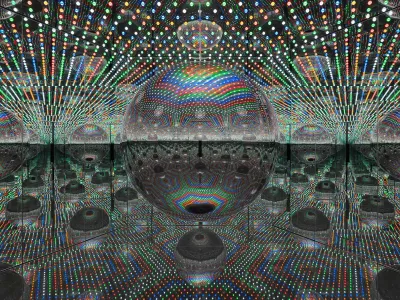

Yayoi Kusama at Victoria Miro

Image Credit: ©Yayoi Kusama/Courtesy Victoria Miro and OTA Fine Arts Yayoi Kusama’s latest is guaranteed to draw a crowd. Victoria Miro has pulled out all the stops for its 14th show with the 95-year-old artist. By the entrance, there’s a pot of multi-colored tokens on a plinth; take one and queue up fairground-style for a ride in the artist’s newest “Infinity Room,” titled Infinity Mirrored Room – Beauty Described by a Spherical Heart. If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to be stuck inside a giant disco ball, this is it. There’s no escape from the inside once the faux elevator doors close. The mirrors and flashing LED lights are instantly discombobulating but after a few seconds your eyes adjust. During my turn, I had the feeling of being an extra in Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon and Saturday Night Fever all at once. Instagram-friendly and playful it definitely is. “An illusion of life in our transient world,” per Kusama’s words—the jury’s still out. For anyone who entered Kusama’s “Infinity Room” at Tate Modern a few years ago, Victoria Miro’s feels less ethereal, less cosmic, and more jarring. The LEDs pulse all sorts of colors before temporarily resetting to default white light. A mirrored orb hangs in the middle of the room and the honeycombed, mirrored walls make sure you’ll know the back of your head like the back of your hand by the end of it (five minutes for each slot, I was told, although 60 seconds is enough). It’s a gimmick, but it’s fun.

Upstairs, two of Kusama’s stuffed fabric tendril installations hang from the gallery’s exposed rafters. One of those works, titled Death of Nerves, drops 50 foot through a hole to the ground floor. The artist’s trademark polka-dots are emblazoned on these sinuous forms. On the walls, many of her bold paintings hang salon-style on white walls that have also been given her spot treatment. “They feel even more endearing, conveying a strong impression of Kusama’s sense of humor and her fluid, free-running lines,” poet, curator, and critic Akira Tatehata said during a walkthrough. The exhibition is indeed light-hearted. These works are painterly and a little rough, and I must admit, I’m not a fan of their “dynamic configuration” hanging, but perhaps this show isn’t designed to be taken too seriously.

Of the sculptures on the outdoor deck overlooking Miro’s pristine, algae-covered pond (an artwork in its own right), Ladder to Heaven is the most compelling. Standing at over 13 feet tall, the polished, stainless-steel work—perforated with polka dots, naturally—is the latest in Kusama’s series of ladders and reaches into a mirror, or “an expansion of space,” as the artist writes in the exhibition description.

-

“Turner Prize 2024” at Tate Britain

Image Credit: Photo Keith Hunter/Courtesy Tramway and Glasgow Life The Turner Prize is quieter these days. Its electric heyday during the ’90s, when artists like Damien Hirst, Chris Ofili, and Rachel Whiteread won, is certainly over. Today, its relevance is being questioned, and for good reason. The prize’s significance and competitive nature were seriously interrogated in 2019, when the four shortlisted artists asked to share the spoils—and the jury agreed. While the Turner Prize has long drawn headlines for the shocking work on view, lately those headlines have focused on everything but the art, like the artists sharing the Prize or artist Tai Shani sporting a “Tories Out” necklace to the 2019 ceremony. I yearn for a return to art on view doing the speaking.

This year, artists Pio Abad, Claudette Johnson, Jasleen Kaur, and Delaine Le Bas are striving to ramp up the volume and drag the Turner from mediocrity back to the center of the avant-garde. The winner, chosen based on the shortlisted artists’ works now on view at Tate Britain, will be announced on December 3.

Reflecting on her experience growing up in Glasgow in a South Asian family, Kaur offers a red Ford Escort draped in an oversize cotton doily as the car’s speakers blare a mixture of hip-hop, pop, and Islamic devotional chanting. It feels like the most Turner Prize–esque of this year’s entries, and she’s my pick to take home the prize.

Johnson’s unfinished portraits in pastel, oil stick, and gouache are moving enough, but they’re nothing we haven’t seen before, especially given how important she has been to British artistic history. That she wasn’t nominated sooner is shame. Le Bas’s installation delves into her Roma roots, while Abad’s weighty, dense drawings, etchings, and sculptures unpack cultural loss and colonial histories of the Philippines. The rest of these entries are all a bit underwhelming, like the current iteration of the prize itself.

-

Francis Bacon at National Portrait Gallery

Image Credit: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd/©2024 The Estate of Francis Bacon, All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage It’s surprising that it’s taken until now for London’s newly refurbished National Portrait Gallery to organize a Francis Bacon show, though it’s worth noting that the artist isn’t represented in the museum’s permanent collection. The exhibition’s curator, Rosie Broadley, recently pointed out that Bacon didn’t paint people “who fit the Portrait Gallery’s collecting criteria”; George Dyer, Bacon’s lover in the 1960s, for example, is not someone the gallery considers having “made a significant contribution to British history or culture,” she added.

Given that the museum has left Bacon out in the cold, it’s a bit on the nose that this exhibition, titled “Human Presence,” explores just how Bacon challenged the conventions of portraiture. With 55 portraits, painted between the 1950s and ’90s, this exhibition is as haunting as you’d expect from a Bacon show. Broadley maps Bacon’s lost lovers, emotional turmoil, and lust over the course of his career, along with the artists he hung out with, like Lucian Freud. Bacon’s paintings, charged with longing and suffering, are on full view. They make for uncomfortable, albeit welcome, viewing. Among the most moving portraits are those of Bacon’s ill-fated muse, Dyer, who died by suicide in 1971 at 36. Bacon’s “Black Triptychs,” painted in the wake of Dyer’s death, show the pathos of Bacon’s approach to portraiture—and how he redefined the genre.

-

Claude Monet at Courtauld Institute of Art

Image Credit: Photo Alain Basset/Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon/©Lyon MBA Monet’s paintings of waterlilies are iconic. His paintings of smog-covered London, less so, and that’s a shame. The 21 works at the Courtauld, being shown in the UK for the first time, evoke the artist’s mastery of light and adept skill at depicting atmosphere. The London sunshine, forced to work harder to break through the thick soup of burnt coal over the Thames, distinguishes the French Impressionist’s London scenes from those of his homeland. “London is more interesting that it is harder to paint,” he wrote in 1901 to his wife, Alice, “the fog assumes all sorts of colors.”

Views of the Houses of Parliament, Waterloo Bridge, and Charing Cross Bridge all feature here. Monet first showed his London-inspired series in Paris in 1904 and was apparently desperate to show the paintings in London the following year, but those plans never came to fruition.

This exhibition is a must, a calm, mediative antidote to the crowded commercial chaos that is Frieze. Be sure to book your tickets now—they’re selling out fast. -

Mire Lee at Tate Modern

Image Credit: Photo Oliver Crowling with Lucy Green/©Tate Standing in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall when it’s empty is an experience, but entering the space after it’s been reimagined as an industrial womb, this long gallery is haunting, disturbing, and above all brilliant. Many artists would fold at the task of turning the massive space into something compelling, but Mire Lee, who showed at the 2022 Venice Biennale and had an acclaimed New Museum solo in 2023, has created a monster—and it’s excellent.

Titled “Open Wound,” a huge, grinding turbine is suspended as the centerpiece of the installation, with pink fleshy hides drape along it. It’s gross, but I found it hard to stop staring. The machine is a reference to Tate Modern’s original use as a power station (it housed coal and oil-fired turbines). Other skeletal forms hang around it, also covered in the giant skins. Have they been peeled off humans, or do they represent something more disturbing? The work is open to interpretation, but it certainly feels like Lee is forecasting our impending extinction.