When I arrived at William Monk’s cavernous Brooklyn studio last month, the British painter was putting the finishing touches on a series of paintings soon to be crated up and shipped for Pace’s solo presentation of his work at Frieze London.

Formerly the studio of painter Dana Schutz, the space feels like a cross between a warehouse and a chapel. Monk’s large-scale paintings hung on each wall, which stretched two stories to the ceiling, like a psychedelic Stations of the Cross.

“I’d been with these paintings for a year,” Monk said, standing before a half-finished canvas. “And this morning there were just these tiny gaps of raw canvas, little white dots. I had to kill them.” He laughed at his own choice of words. “If your eye stops there because of something I didn’t intend, that’s bad. You kill it. The eye should move where you want it to go.”

That instinct—to control what’s seen and what’s left hovering—has always defined Monk’s paintings. His new body of work, now on view at Frieze, began during a residency at the Neuendorf House in Mallorca, a 1970s modernist compound designed by John Pawson and Claudio Silvestrin. Alone for a month, Monk found himself caught in a kind of luxurious purgatory.

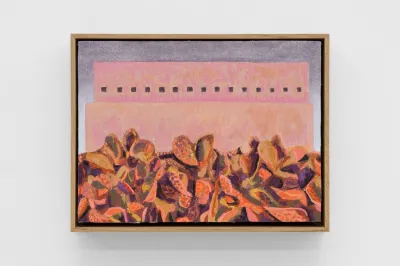

“It was like Waiting for Godot with one character,” he said. “Time stood still.” Out the back of the house was a patchy cactus garden. “I photographed one cactus bush and collaged it over and over again until it became this all-over field, like a Jackson Pollock pattern,” he said. Those cacti now populate his new paintings—vivid, obsessive forms, alternately serene and foreboding.

The works extend the mythology of his 2023 Ferryman series, in which he reimagined the figure of death through the lens of his own memories. As a child, he watched the Beatles film Yellow Submarine on repeat; its surreal colors and floating architecture became part of his internal landscape.

“Before my real memories started, that film was already there,” he said. “So when I imagined death, I thought of that world—the way it makes the unknown seem almost playful.”

In the new paintings, the ferryman evolves into a sentinel: a solitary figure stationed on an undefined Mediterranean island, surrounded by cactus, water, and rock. “He’s waiting,” Monk said. “Living small, contained, and waiting.”

Monk, who moved from London to New York a decade ago, has built a career on slow, methodical vision. His brushwork—dense, rhythmic, almost musical—recalls both Seurat’s pointillism and the rolling textures of late Bonnard.

“My surfaces are always active,” he said. “It’s about rhythm—changing steps.” The solo booth at Frieze is, in a way, a homecoming for an artist who made his bones across the Atlantic.

Marc Glimcher, Pace’s CEO, told ARTnews that he sees Monk as “a mix of Kubrick, the Beatles, Seurat, and Bonnard—the bastard child of those four.” When he first visited Monk’s studio, Glimcher said, he was struck by the combination of professorial awkwardness and absolute virtuosity.

“Each painting nearly kills him,” Glimcher said. “You look at them and think, how did he survive that?”

For Pace, Monk’s show at Frieze London marks more than just the debut of new work; it’s a quiet manifesto about how the gallery believes primary-market art should be valued.

“We had a rule,” Marc Glimcher said. “Ten percent every two years. That was how it used to be done. Prices rose slowly, by percentage—not by auction results.”

Glimcher said he sees Monk as a case study in resisting the boom-and-bust logic that has gripped much of the market and led some artists to ruin. “Will makes very few paintings. We escalate the prices gently. He hasn’t even entered the auction cycle yet. We place the works with people who love them, not who flip them.”

Monk is careful when talk turns to value. “My paintings have gone up, sure,” he said, “but New York finds a way to take it all back.” He smiled, half self-deprecating, half sincere. “When I was younger, my work was worth nothing, and I felt rich. Now it’s worth something, and I feel broke.” Still, he’s grateful for Pace’s deliberate pace. “It keeps me out of the noise,” he said.

For Glimcher, that patience is the point. “We’re back to the real thing,” he told me on the balcony outside his office. “Enough of artists who skyrocket and flame out. Monk’s the opposite: slow, steady, serious. After the last two years, people’s attention has reset. They’re ready for nuance again.”

In that sense, Monk’s return to London—his first show there since 2019—feels like a homecoming in more ways than one. The Sentinel paintings, with their glowing cacti and long shadows, are meditations on solitude and endurance but also on the act of seeing itself: what the eye notices, what it misses, what it kills. In the quiet of his studio, surrounded by his guitars and the faint hum of Yellow Submarine, Monk seems to have found a rhythm that resists the speed of everything around him.

“I just want the work to last,” he said, looking at a canvas propped against the wall. “If I can keep it alive—if it can keep me alive a bit longer too—that’s enough.”